Welcome, subscribers! Today, we share lengthy pitches for companies in biosciences, energy drinks, and analog semiconductors.

Read on to learn more. 📕👇

Your support is appreciated. If you enjoy this issue, please forward to a friend or colleague!

Disclaimer: Nothing here constitutes professional and/or financial advice. You alone assume any risk with the use of any information contained herein. We may own positions in the securities listed. Please do your own due diligence.

To the investment managers who read this, you can send us your letters at elevatorpitches@substack.com or on Twitter (and Threads!) if you’d like to be included in a future issue.

Let’s get to it.

RGA Investment Advisors provided a deep dive into their newest holding, Danaher Corporation (DHR). Three months ago, Third Point also discussed Danaher, albeit briefly.

Purity in the Crown Jewel of Bioprocessing:

One of the companies we have studied for many years, patiently waiting for the opportunity, finally gave us what we were looking for: Danaher Corporation. During the second quarter we bought a sizable amount of Danaher. We have analyzed the company, its spun off entities and studied its history over the years, though we had never purchased shares. This was partly due to questions about company end-markets and valuation, and partly due to impatience on our part. Sometimes certain opportunities simply fall into place.

During several of our recent letters we have articulated and explained our interest in the life science space, especially the tools and instruments companies and Danaher happens to be perhaps the premier asset in the space. Before explaining why, it is worth highlighting why Danaher has been a company of interest for so long. Danaher was founded by brothers Steven and Mitchell Rales in 1984. The brothers focused on acquiring manufacturing companies and applying their version of Japanese kaizen in a process they named the Danaher Business System (DBS). DBS is described by Danaher as follows:

…the DBS engine drives the company through a never-ending cycle of change and improvement: exceptional PEOPLE develop outstanding PLANS and execute them using world-class tools to construct sustainable PROCESSES, resulting in superior PERFORMANCE. Superior performance and high expectations attract exceptional people, who continue the cycle. Guiding all efforts is a simple philosophy rooted in four customer-facing priorities: Quality, Delivery, Cost, and Innovation.[13].

Danaher is structured as a holding company/conglomerate, focused on continually deploying retained earnings into new businesses. As the company evolved and matured, the focus on manufacturing broadened in end-market terms and narrowed in its affinity towards growing end-markets and high recurring revenues. This led Danaher into the life science space, where the razor-blade business model is especially prevalent.

We mentioned that Danaher today is a premier life science company and this resulted from an acquisition closed shortly before COVID began. Larry Culp had retired as Danaher’s CEO in 2015, before joining GE in 2018. Within a year of taking the reigns at GE, Culp sold Danaher GE’s Biopharma business for net proceeds of $20[14] This move was interesting to us for two reasons: It was transformational for Danaher in making life sciences the company’s largest and fastest growing end-market.

It was transformational for Danaher in making life sciences the company’s largest and fastest growing end-market.

It was transformational for Danaher in making life sciences the company’s largest and fastest growing end-market. It was Culp specifically who led Danaher down the road into life science with a series of acquisitions over his decade and half tenure, including assets like Leica Microsytems and Beckman Coulter. This almost seems like a parting gift.

With life science tools and instruments now the company’s largest end market, the stage was set to focus on the company. For most of its history, Danaher had functioned as a traditional conglomerate–acquiring assets without truly integrating them–while operating in an unconventional manner. DBS is at the heart of what makes Danaher unconventional, but the company has also been willing to divest and spin assets to reinvent itself around a core focus. Danaher’s push into a pure-play life science company was cemented with the announcement in late 2022 that it would spin off its Environment and Applied Solutions segment into a standalone company since named Veralto. The confluence of Danaher’s pure-play life science phase of its life and our intrigue in the sector situated us perfectly to capitalize on the opportunity. Our excitement was piqued as Danaher’s stock suffered through most of the first half of this year on falling revenue expectations in life sciences. There were three primary culprits behind the slowdown:

Lower demand for the COVID-19 vaccine and COVID-related diagnostics

Falling funding at early-staged biotechs, leading to lower levels of spend on new instrumentation and consumables

Slowing demand from CDMOs (the companies who manufacture most biologics) due to the burn down of excess inventories built up during the COVID supply chain crisis

We will focus the majority of our conversation below on this third bullet, as in our estimation it has been most impactful and it pertains most directly to the piece of Danaher we find most alluring–the Biotechnology segment comprised of Cytiva, which as of today is the combined GE Biopharma (2020) and Pall (2015) acquisitions. Bioprocessing is the manufacturing process through which a cell or cells are scaled up in number in order to filter out and then, harvest specific pieces or output of the cells themselves. This is the process through which biologics, vaccines and now increasingly cell and gene therapies are made through. It is an oligopolistic market, with a small number of critical players and extremely high barriers to entry—two to four companies compete in any one of the key sub-segments. Danaher owns anywhere from 35-40% market share in the industry.[15] Although many fawn over the criticality of a company like ASML in empowering the semiconductor industry, the bioprocessors are similar for the biotechnology industry. The processes are complex, entailing both upstream and downstream components, with Cytiva the most comprehensive, vertically integrated and unique offering in the industry. Cytiva is especially dominant downstream, where bioprocessors make the most money and margin and the offering is truly differentiated. Moreover, once a pharma or biotech commences their clinical process with Cytiva’s components, those pieces become “spec’d in” guaranteeing a long-term revenue stream. These are predominantly consumable revenues by nature with over 75% of revenues derived from recurring sources.

Danaher closed the GE Biopharma (Cytiva) acquisition on the eve of the COVID pandemic. Typically, Danaher would operate a large, acquired business as a standalone business unit; however, Pall and Cytiva have a high degree of customer and product overlap. The plan had been to integrate these two units; however, with COVID and the intense demand for bioprocessing product as well as the complex operating and supply chain environment, Danaher prioritized meeting customer needs over the planned integration. With COVID now behind us, supply chains largely in order and more balanced customer needs, Danaher is finally pursuing a true integration. This will unlock both short and long-term benefits. First, a unified salesforce and a better cross-sell motion will drive better sales; second, and more importantly, a unified R&D effort across upstream and downstream assets will allow for a more harmonized product roadmap that could truly solve some of the biomanufacturing industry’s foremost pain points. While it will take time for Danaher to realize these R&D advantages, we believe the longer-term benefits could be profound as Danaher now owns the most complete portfolio and can build out simpler, more harmonized workflows. In today’s myopic environment, few are focusing on this critical long-term evolution.

As revenue expectations have come down for Danaher and other bioprocessing companies, some of questioned whether these newly lowered expectations are the consequence of temporary forces that inevitably will recede or signs of a more permanent step-down from the double-digit growth rates witnessed over the last decade into a new-normal in the single digits. As we have pursued our work, the answer is clear in our minds that these forces are temporary rather than permanent, meanwhile the valuation of Danaher has moved to a point where it is reflecting a degree of permanence on an artificially low level of earnings.

The following summarizes the findings of our conversations with industry practitioners from the CDMO and biotech space. The typical CDMO contracts with its customer to what level of consumable inventory should be held over time. This was typically in the 6 month range, due to consistent volumes of biologic manufacturing and a two-year or less shelf-life on the critical pieces. This 6 month range was bumped to upwards of one year of inventory and in many cases nearly 18 months of inventory. Further, many put in for weekly orders on critical pieces when monthly orders formerly sufficed, as the more frequent cadence bumped the purchaser up the priority list at the vendor. These actions made sense during COVID when inconsistent supply chains imperiled the ability of some pharmaceutical and biotech companies to bring life-saving drugs to market.

The problem is that CDMOs and their customers made such agreements with hand-shake arrangements rather than formalized re-writes of their contracts and had no system in place to track inventory and to which customer’s account to attribute the purchase of standardized inventory pieces. Therefore, contractually, CDMOs were committed to purchasing certain volumes of consumables with the bioprocessing companies like Danaher; however, the CDMOs customers were theoretically responsible for reimbursing such purchases though not necessarily bound.

These problems were confounded by challenges at the FDA for the industry. Although COVID saw a surge in funding for the biotech industry, it created significant bottlenecks in development and approvals at the FDA. These forces have weighed on bioprocessing demand with a lag, as it resulted in a much slower pace moving indications through the clinic. The FDA is committed to resolving these problems and has expressed its intent on “if not exponential, at least some logarithmic progression towards more and more gene therapies being approved.”[16] Part of the improvement is facilitated by moving FDA staff off COVID-specific problems and approvals. Another key pillar is facilitating enhanced manufacturing processes and protocols, which would accrue benefits to the bioprocessing industry. Progress is already palpable with Sarepta’s Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy garnering FDA approval despite a panel initially recommending otherwise.[17]

As 2022 drew to a close, there was a sudden realization across the industry that a) supply chains had finally normalized; and b) given the normalization of supply chains there was far too much consumable inventory in the system. Before the bioprocessing companies truly caught wind of this, the CDMOs and pharma/biotech customers had to sort out who would pay the bill for in-place commitments and future were revised and renegotiated. Understanding these dynamics made clear to us that it was difficult for the bioprocessors to get visibility into the trends as they stand today; however, triangulating with other industry reference points, it equally became clear that strong growth for the industry was truly a “when not if question.” We find such setups incredibly attractive given the obsession of most market participants with identifying the precise timing of an inflection. Importantly, several key forces align to suggest this inflection will take shape sooner rather than later. These include:

A normalization of inventories and return to steady-state consumable purchases.

Accelerating FDA approvals, breaking the COVID-induced slowdown, which has weighed on the last several years of activity. Approvals are running well ahead of 2022’s painfully slow pace, especially strong in biologics which have a more pronounced revenue impact for the bioprocessors.[18]

Biologic prescription volumes troughed in the Summer of 2022 and now are accelerating comfortable into double-digit year-over-year growth. Importantly, prescription volumes translate nicely into accelerating volume needs, supporting consumables demand.

Moving beyond COVID vaccine-related demand from challenging year-over-year comparables

Rapid uptake of GLP-1 inhibitors which both drives increased investment needed to support demand and increased investment from competitive offerings (same targets, new formulations as well as additional targets) and Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk investing their proceeds in novel areas. Plus, from a sentiment perspective the success of GLP-1 inhibitors hammers home how much meaningful change for humanity and investors alike comes from the biotech sector.

Breakthroughs during COVID in modalities like mRNA, with a clinical pipeline in the space that never would have happened otherwise, which will reach more mature and volume-demanding stages of the clinical development curve in the 2025-26 timeframe. In fact, several industry experts we spoke to think this cyclical downturn today might sow the stages for overly tight supplies as growth surges for consumables demand accompanying clinical maturation. The above explains our attraction to the bioprocessing space. Below let us point out the specific reasons why we centered our interest on Danaher in particular:

History: Danaher has a long history of prudent capital allocation and this is an outstanding moment in time for acquisitions in the life sciences.

Philosophy: centered around a unique and proven operating philosophy (DBS).

Timeliness: Danaher will spin off the non-life science assets at the end of the third quarter and become a pure-play in the sector for the first time in its history. More importantly, Danaher is strategically integrating Pall and Cytiva for a unified go-to-market motion.

Valuation: Post Veralto spin, Danaher is trading for approximately 21x our view of normalized earnings, which is at a slight premium to a market multiple for a company that will grow at a far swifter pace, for a longer duration. Further, this 21x is understated given the high component of amortization in Danaher’s reported earnings that stems from their acquisition-heavy strategy. Amortization alone adds up to about $1.90 hit to EPS, which would reduce the P/E ratio by upwards of 3 turns. In Danaher’s case, we think EBITDA is a great proxy for true earnings power and free cash flow generation. If we stack up the last three full years of EBITDA (2020-2022) post-spin and after expensing corporate overhead, the company trades for an EV to average EBITDA of 18.38x. Essentially, when viewed through this prism, between normalized earnings power and looking past non-cash amortization, the business trades at a slightly below S&P earnings multiple for a much better quality and growth profile with an inevitable cyclical upturn looming ahead.

In their latest quarterly letter, Immersion Investments included an in depth look at their thesis for energy drink maker, Celsius Holdings (CELH). We share an excerpt below. Click through to read Immersion’s thoughts in their entirety.

Celsius Holdings, Inc. (CELH – Doubted Champion)

Celsius Holdings Inc. (CELH – Doubted Champion) is the owner of the Celsius brand of energy drinks. Celsius has been a day 1 holding of the partnership and through organic appreciation, coupled with our significant reduction of Basic-Fit shares at the beginning of the third quarter (discussed in the second quarter letter), has grown to become the number 2 position over the last six months. Despite a tremendous runup in shares over the past several years, we think Celsius remains underappreciated and undervalued.

1. Based on latest scanner data, Celsius holds a roughly 6% share of the U.S. energy market over the last twelve months, making it #3 behind Monster and Red Bull. We believe Celsius can continue to grow and become a significantly larger business for several key reasons…

a. Celsius holds a 20%+ share on Amazon and major Florida markets (Miami, Orlando, and Tampa), its most mature markets, and nearly 20% share in New York and Boston. These analogues provide solid evidence that Celsius is capable of being significantly larger than it is today.

b. Despite industry-leading velocity growth, Celsius’ shelf space allocation to date has meaningfully lagged Monster and Red Bull.

c. Celsius grows the category. The brand attracts new users and does not solely rely on stealing share to grow.

d. Celsius is early in its international expansion journey.

2. Analysts mismodeling inherent operating leverage in the business

a. Despite strong projected revenue growth, the estimated flow-through of that revenue is nonsensical, given the people and capital-lite nature of Celsius’ operating model.

Business Background:

Originally founded in the mid-2000s, Celsius spent more than a decade as an obscure preworkout drink for gym rats in the eastern Florida fitness community. Around 2017, the company appointed CFO John Fieldly to the CEO position and pivoted its marketing message to one of overall health and well-being, coining the current slogan “Live Fit”.

Celsius branding circa-2012:

Celsius branding today:

The brand began to gain momentum, growing from $17mm in sales in 2015 to $314mm in 2021, due to distribution agreements with a variety of independent distributors within the AnheuserBusch, PepsiCo, Keurig Dr. Pepper, and Miller Coors networks. Total U.S. doors/locations grew from 64,000 at the end of 2019 to 135,000 at the end of 2021. Celsius reached a tipping point in August of 2022, when it announced a long-term distribution agreement with PepsiCo, making it Celsius’ sole distribution partner in the United States and “a preferred partner” globally. As part of the deal, Pepsi invested $550 million into Celsius in exchange for convertible preferred stock, paying a 5% annual dividend. If converted, Pepsi would own 8.5% of Celsius. During its journey from a small $20 million product to a meaningful energy contender with nationwide distribution, Celsius has shown industry-leading shelf velocity. Said differently, sales per location have grown rapidly, in step with new distribution, indicating that consumers are resonating with the product and buying it in greater and greater frequency. Celsius is not simply growing because they are getting new doors, they are growing because people like the product. By our math, sales per location have compounded at a 35% annual rate of growth for the past four years. This vastly exceeds a category exhibiting low-teens growth rates.

Today Celsius is a $1 billion revenue business and has achieved 97% ACV (All commodities volume – measurement of % of market reached) vs. 80% at the time the Pepsi deal was announced. Trailing twelve month gross and adjusted EBITDA margins stand at 45% and 17%, respectively. The company has no debt and $680 million in cash on its balance sheet. The market capitalization (based on our share count of 86.4 million, which assumes conversion of the preferred, and a $152 stock price) is $13 billion. Celsius operates in a similar manner to Monster Energy. It is a capital-lite licensing business, responsible for developing and marketing its product but is not responsible for its manufacture or distribution. Over the last twelve months, Celsius has spent $12.6 million in capital expenditure to support $952 million in sales, or roughly 1 penny for every dollar of sales.

The Opportunity:

Despite its significant success to date, we think the opportunity in the shares remains as robust as it was when we first invested a little over two years ago.

In the medium term (3 years) we think that Celsius can reach a 20%+ share in tracked retail channels (grocery, convenience, retail vs. untracked channels – club, foodservice, online, fitness) in the United States. This is supported by actual market share data in Celsius’ oldest markets, Amazon (20% share) and South Florida (25% share), and nearly 20% shares in New York and Boston, which are more nascent relative to the former markets. This could happen sooner than we’re anticipating. The latest short-term (12 week) scanner data points to a 10%+ share for Celsius and the product maintains the healthiest shelf velocity in the category. Burgeoning products like Alani and Ghost have gained significant shelf space over the last twelve months but takeaway growth is significantly worse than Celsius. Sales per distribution point (velocity - effectively same-store sales) grew 26% in the last 12-week period reported by Nielsen, vs.+16% for Alani and -37% for Ghost. Industry leaders Monster and Red Bull grew 3% and shrunk 12%, respectively. This strongly supports an argument for Celsius gaining further shelf space in existing doors. Today, Celsius has 14 SKUs per store vs. 8 a year ago. Monster and Red Bull average 25 SKUs per door, indicating further room for Celsius to grow. The opportunity is particularly ripe in the convenience channel, where Celsius under-indexes. Celsius’ share of convenience is lower than in all other channels, due to a historic lack of distribution, which is being remedied with Pepsi. Celsius still averages less than 10 SKUs per shelf in convenience (lower than the company average), while Monster and Red Bull tend to have more SKUs than in other retail locations. This is despite Celsius shelf velocity in convenience growing faster than the latter two. Increased distribution in convenience is especially important because it is the largest channel for energy drink sales (~60% of tracked channel sales). We don’t think shelf expansion will necessarily come at the expense of Monster or Red Bull. Celsius appeals to a different audience than the typical energy drink. Management has disclosed that 40% of Celsius consumers are new to the energy category and the brand has a close to 50/50 male/female split vs. 70/30 for most competitors. We attribute this to Celsius’ branding, which is ‘softer’ than the typical masculine symbolism of Monster and Red Bull. The end result being that much of Celsius’ presence in retail is through expanded shelf space taking from other categories (soda, RTD coffee, etc.) rather than by taking from incumbents.

Outside of the United States, Celsius has significant opportunity to grow through the global PepsiCo distribution network. International is a largely untapped market for Celsius. It has had a small and growing presence in China and Nordic countries for about a decade but it has yet to receive the appropriate time and attention from management to achieve scale. Red Bull is a global business, with the product originating in southeast Asia and the company today generating most of its sales outside the United States. Monster has grown its international business to ~$2.5 billion over the past ten years and accounted for nearly 40% of sales for the first six months of 2023. The energy drink market generates ~$50 billion in sales globally, 55% of which come from outside the United States. Clearly, energy is a global category. By comparison, international made up just 4.5% of Celsius sales during the first six months of the year. Management has indicated its intention to carefully build an international presence with PepsiCo starting in 2024 in established markets like the UK, Canada, Germany, Japan, and Australia.

Significant margin expansion potential coupled with the aforementioned top line growth opportunities make Celsius an even more interesting opportunity. Over the next couple of years, we believe Celsius has a very good chance of seeing 10+ percentage points of margin expansion, to roughly 30% adjusted EBITDA margins, with a very high conversion to free cash flow, given minimal capital expenditure and no debt expense in the business. Our reasoning is simple. Monster Energy, which operates essentially the same business as Celsius, can generate mid-30s EBITDA margins and we see no reason why Celsius can’t approach that level over time. At a minimum, we believe that current sellside estimates are needlessly low (20-to-21% for the next three years). Why? Current margins are in the high-teens and any analyst showing a three-year bridge to 30% from 17% will be laughed out of the room (we have no such concerns). Second, there is no incentive to give management a bogey it can’t beat so it’s safer to set a “reasonable” hurdle and let management walk right over it. And three, management has historically never discussed a long-term EBITDA margin target until this past September at a bank-sponsored investor conference when they claimed margins could approach Monster’s margins.

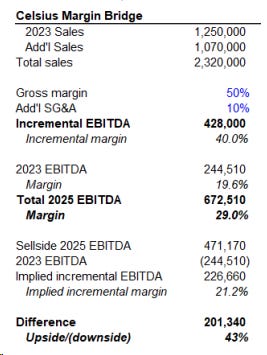

Below, we outline how we believe additional revenue will flow through to EBITDA. The revenue figures are based on consensus estimates. We have reason to believe Celsius can beat sales estimates but that is not the point of this exercise. We forecast a 50% gross margin on new sales and 10 cents of additional selling, general, and admin expenses for every additional dollar of revenue generated. This yields $672.5 million of adjusted EBITDA in 2025 vs. current estimates for $471 million. We believe our numbers are more reflective of reality because they most clearly align with Celsius’ people and capital-lite business model. However, consensus figures place 2025 EBITDA margin at 20% vs. 19.6% for 2023, basically assuming zero operating leverage, which is absurd, given the fact that Celsius’ business model allows for very high flow-through of additional revenue. We do not understand what is being baked into these estimates. It is possible that analysts are expecting no operating leverage on selling & marketing expenses. If we hold S&M flat at 19% of sales for the next two years, we get to $200 million of additional spending, which accounts for roughly two-thirds of the implied $300 million increase in operating expenses for the next two years. This seems improbable, though. S&M expenses can be leveraged. Scaled beverage companies spend 4-to-10% of sales on this line item, vs. Celsius’ comparatively bloated 19% today. Even if it were true that Celsius maintains elevated spending for the next two years, we don’t understand the origin of the other $100 million in new spending. That implies 1,000 additional hires at a $100,000 average annual salary. Celsius today employs less than 500 people. Tripling headcount in two years seems like an absurd assumption. The company should actually require fewer people today because it is now operating with a single master distributor as opposed to pre-2023 when they had hundreds of individual distributors that required significantly more manpower to process and coordinate shipments, receivables. etc. On this basis alone, consensus numbers seem overly pessimistic. We also have a fantastic analogy in the Monster/Coca-Cola deal announced in 2014 that made Coca Cola the preferred global distribution partner of Monster. In the three years following this deal, Monster EBITDA grew to $1.28 billion from $777.8 million in 2014 on a $904.1 million increase in sales. That is a whopping 56% incremental EBITDA margin. Our 40% incremental margin from 2023 through 2025 seems paltry in comparison. Our second proof point, which speaks to the concern about scale in the business, is that when Monster went from $1 billion to $2 billion in sales (basically where Celsius is today), the company saw incremental EBITDA margins of almost exactly 40%.

The main risk to this business is that management does not adequately support the brand and allows it to lose momentum. The energy landscape is riddled with the corpses of companies that tried and failed to compete with Red Bull and Monster. In our initial work on this name, we were told that no brand can break the mystical 10% share mark (Celsius is basically there). We think this is because most brands do not have the dedicated support of a distributor like Pepsi that can secure adequate shelf placement. Second, many do not have the capital to invest behind the brand via store placements, promotions, commissions, and marketing. Bang Energy was the one brand that most recently had the best shot at cracking 10% share, peaking out at 9% in 2019. Bang’s failure is often attributed to its ostentatious founder, Jack Owoc, who supposedly through shear personality and willpower catapulted Bang into the stratosphere and eventually got too close to the sun and collapsed in upon himself like a dying star (Google him for fun stories on the various antics and lawsuits). Whatever his personal failings, we don’t think this narrative is quite accurate. Scanner data from when Bang was approaching 8% share reveals that the brand was already losing momentum and seeing shrinking sales on a per-store basis. In other words, the brand wasn’t resonating with consumers, it was simply penetrating more doors. There are many theories for why this was the case, but our belief is that Bang isn’t a differentiated product. It didn’t bring anything new to the category and relied too heavily on taking share from Monster and Red Bull. Bang, like the latter two brands, relies heavily on young, white males between the ages of 18 and 35. They were able to gain some success but couldn’t maintain momentum because they weren’t tapping into a new type of consumer. This is in stark contrast to Celsius, which is growing the category and has maintained strong same-store growth as it reaches 10% share.

Ensemble Capital shared lengthy overviews of a few of their holdings in their latest letter, including for Analog Devices (ADI) — which we include below.

Analog Devices: Analog Devices, known in the industry as ADI, makes semiconductor chips that predominantly operate at the boundary of the physical world and the digital world, more commonly referred to as analog and mixed signal chips. These chips usually play a supporting role to the sexier “digital brain” that is the latest and greatest processor from Nvidia, Intel, AMD, Apple, or Qualcomm. While the digital brains get a lot more media attention, the supporting analog chips are as vital as those big expensive digital processors in driving value in electronic devices, which are becoming ubiquitous and intelligent throughout our lives.

Anything with an on-off switch requires lots of these analog chips if it is going to relay input and output information with the physical world as well as manage the electrical power supply feeding the device. While these analog chips are relatively inexpensive to manufacture and distribute, it takes a long time to design and build a catalog of literally thousands of specific products to create the scale that makes them economically attractive businesses with a reputation of dependability and quality.

What’s unique about this class of chips is that companies making them do not need to make the huge investment bets that digital chips require in both R&D and manufacturing to stay ahead on the Moore’s Law performance treadmill. Analog chips usually use manufacturing equipment that’s several years or even decades old, which are much cheaper to buy than the latest and greatest that digital chips require.

In addition, consolidation has reduced the number of players in the semiconductor industry to a few big players globally and just a handful in the US, with analog chipmakers demonstrating a focus on strong returns on invested capital, high levels of free cashflow, and good competitive advantages built on scale, reputation, and a cornered talent resource of specialized analog engineers that we’ll explore further.

To understand why we believe ADI is both different and valuable, we have to delve a little bit into the technicalities of semiconductors. While we think of chips as “thinking” in ones and zeros, the real world does not operate on ones and zeros. The forces in the physical world have more of a continuous analog waveform that is not binary – examples of these are light color and brightness, sound frequency and volume, pressure, temperature, etc.

Mixed-signal chips will take those continuous signals and transform them into digital data that digital processors and memory chips can understand. Then the digital chips can operate on that data to compute new information or activate an output signal, which are translated back for consumption in the physical world by a mixed signal chip. Analog chips perform a similar role, but usually in the realm of power regulation and communication. Analog and mixed signal chips are often made by the same companies and sometimes referred to interchangeably.

As technology has broadly penetrated our world and everyday lives, semiconductors have also done the same as the underlying hardware substrate. Moore’s Law has allowed their capabilities to grow, and their cost and energy consumption to fall at an exponential rate, which has driven their adoption and use in a broad range of applications in all industries, bringing us to where we stand today, on the verge of ubiquitous connected intelligence.

As devices are able to do more and become more intelligent, their semiconductor content has increased, relying on more sensors, power management, and communications capabilities. These devices and systems are dispersed throughout our lives… from smartphones to computers, cars, planes, microwaves, ultrasound machines, HVAC systems, cellular radio towers, data centers, factories, etc. Given their role, it’s important to recognize that the more powerful and capable the main digital processor is, the more data it needs to bring new applications and value to market.

A lot of these applications also leverage connected devices – think your smart bulbs or fridge or cars – and all of these applications that can do more, generally require more analog chips to do the “sensing” that creates the data that feeds the application or main processor. In the case of the latest cars, those with adaptive cruise control, fancy smart LED lights, and electric vehicles – which are basically getting close to becoming computers on wheels – the number of chips required is multiples that of vehicles just a few years ago and is 10-100x as many as traditional products we think of as technology products like iPhones, PCs, and game consoles.

Therefore, we believe that the analog segment of the semiconductor market can see faster growth ahead, but without the risk and high levels of ongoing cash reinvestment necessary for the sexy digital brain part of the industry. In analog, the pace of technological change is slower and product cycles are much longer, spanning decades in many cases. This results in sustainably higher returns on R&D and manufacturing investments, along with more consistent secular forecastability. In addition, the markets they sell into are global and across all industries making them relatively less dependent on one or two end markets, like smartphones or the data center.

Companies like ADI and Texas Instruments (which the industry refers to as TI), two of the largest analog companies, have built broad portfolios of tens of thousands of products, each with over a hundred thousand customers who make millions of products that sell billions of units. The product needs and lifecycles across all industries can vary from a year to decades, which is why ADI derives half of its revenue from products that are over ten years old! Historically, the prices of these chips have ranged from less than a dollar to a few dollars while volumes in the billions of chips result in $10-20 billion dollars of revenue for each of these companies at operating profit margins of 30-50%.

Once these chips are designed into customer products, it is generally uneconomical to switch them out for a competing chip because the average selling price is so low relative to reengineering costs, especially when you consider software that is built on top of the designed in hardware. This makes ADI’s products sticky once they are designed in, resulting in a competitive moat that spans across the scale of products and distribution, switching costs, and service capability.

Another source of competitive advantage and value to customers is that unlike digital chip design, there is a lot of “art” or experience-based know-how that goes into analog and mixed signal chip engineering that deals with its own unique set of design challenges. This results in an engineering talent pool that is hard to replicate at new companies or even at customers’ product design teams. Consolidation in the industry has meant that these resources are even more concentrated at the largest companies, which enable them to drive further efficiencies in product development.

Taken together, in most end markets outside of consumer electronics, all of these factors make it hard for a new entrant to build enough scale in any timeframe under a decade to become a profitable competitor.

While consolidation has mostly played out in the industry, increasing complexity, automation, and integration create other avenues to grow revenue and margins, one that ADI has been particularly focused on with the diversity of functional chips it has in its catalog of nearly 80,000 chips. Customers are coming to rely more and more on buying complete solutions from ADI, which is becoming more of a solutions partner rather than just a chip components vendor. This allows ADI to get closer to its customers’ engineering teams and help design and build subsystems comprised of multiple chips that its own engineers have integrated to perform complete functions. Historically, engineers at the customers’ design centers would be buying chips from multiple companies and integrating them onto system boards themselves.

Delivering more complete solutions has enabled ADI to increase its average selling prices and build a higher margin business over time, while also providing further protection from competition and deleterious price pressure effects in the future during more economically challenging times.

Examples of this are battery management and infotainment systems in autos, 5G cellular radio infrastructure, digital systems in healthcare instruments, and smart factories. ADI has targeted and successfully built systems level businesses in these high growth industries.

Based on what industry leaders like ADI and TI are saying and our own broader understanding of trends in various industries, including auto, energy, communications, industrial, and healthcare, it appears that trends in this part of the semiconductor industry is at an inflection point of acceleration. Whereas historically organic growth has trended in the mid-single digits, the next few years are forecasted to grow closer to 10%+ per year. In fact, these companies are so confident in that forecast based on customer conversations that they are allocating billions more in capital to build out new manufacturing capacity to meet the demand.

In the meantime, valuation multiples in this area are reasonably cheap since the semiconductor industry, outside of booming AI related names, has been undergoing an inventory correction as a result of rebalancing from the COVID disruption years. We believe we are at the latter part of the cyclical adjustment that fluctuates around an accelerating secular trend.

The future is bright for analog leaders like ADI and TI, although they are pursuing that opportunity with different business strategies that lead us to currently prefer ADI over TI. However, we believe both could be winners at different stages as the industry evolves to capture the growth opportunity ahead.

Until next time! - EP