Welcome, subscribers! Today, we share pitches for an auto parts retailer and a beverage can manufacturer — plus two other unique ideas.

Read on to learn more. 📕👇

Your support is appreciated. If you enjoy this issue, please forward to a friend or colleague!

Disclaimer: Nothing here constitutes professional and/or financial advice. You alone assume any risk with the use of any information contained herein. We may own positions in the securities listed. Please do your own due diligence.

To the investment managers who read this, you can send us your letters at elevatorpitches@substack.com or on Twitter (and Threads!) if you’d like to be included in a future issue.

Let’s get to it.

Wedgewood Partners provided a lengthy write-up of their new position in O’Reilly Automotive (ORLY) in their latest quarterly letter. The automotive parts retailer has been a massive outperformer over any meaningful time frame but has underperformed this year. Is there a buying opportunity?

O’Reilly Automotive

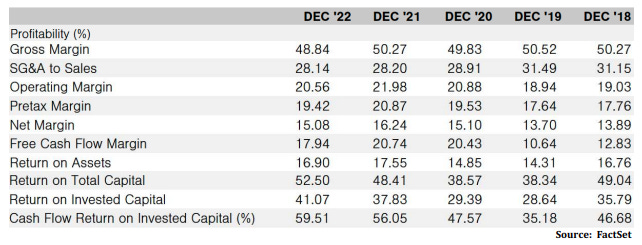

The aftermarket auto parts industry is a retailer’s dream. Such dreams include: market share take opportunities for better operators in a fragmented industry, hard-to-replicate, competitively advantaged, distribution network effects, which increasingly get closer to customers; three decades of consistently positive annual sales comps; recession resistance; consistent new store openings; steady growth from multiple avenues; increasing profitability from company branded products; increasing long-lived “customers” (more and better cars on the road, more cars on the road past warranty and more miles driven); and reinvestment of cash back into the business at expanding margins. Net, net, witness O’Reilly’s stellar profitability profile:

Circa-2023 is delivering an extra gust to these tailwinds in the form of significantly higher financing for both new and used cars. Thus, U.S. automobile owners are literally forced to keep cars longer. As mileage racks up, maintenance and repair bills rack up too.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that global fleet of internal combustion engine (ICE) light vehicles will peak in 2038. In addition, the EIA projects that electric vehicles (EVs) will account for +30% of the global fleet by 2050. We take such long dated forecasts with a grain of salt, yet we do not disagree with the expectation that the auto parts industry has a long pathway of growth. The jury is still out on whether the technological advancements of EVs will render these vehicles mainstream in locales where the extremes of the four seasons are present. As of today, the annual maintenance cost of an EV is less than the cost of an ICE vehicle. That said, the undercarriages of EVs (brake calipers, brake pads, rotors, shocks, etc.) need to be repaired at similar intervals as ICE vehicles.

The U.S. auto parts industry has been largely dominated by the four well-known publicly traded companies – Advanced Auto Parts (including Car Quest), AutoZone, NAPA (owned by Genuine Parts Company) and O’Reilly Automotive. Surprisingly, given when these companies were founded, the U.S. auto parts industry remains largely fragmented. Their respective founding’s: Advanced-Carquest: 1932-1974. AutoZone: 1979. NAPA: 1925. O’Reilly: 1957. By far, the leading two companies in terms of profitability and growth are AutoZone and O’Reilly – then O’Reilly over AutoZone over the past few years - by the nose of a bumper.

Before we get into the modern incarnation of O’Reilly Automotive, we would like to share a short history of the Company. The U.S. retail industry is historically rich in Horatio Alger success stories. We all know the antecedent storyline of such histories. Insomniac entrepreneur, usually already well into their years, start with a single tiny store - and a dream. Countless hours, later family, children, and siblings, then succeeding generations share the founder’s dream. Decades of too many hours of work to count. Some success. Then, better success. Then maybe, just maybe, an IPO. Then rarer still, generational wealth. Many know the story of the Waltons from Columbia, Missouri. Few know of the O’Reilly family from Springfield, Missouri. Fewer still, of George Pepperdine, who, in 1909 founded the Western Auto Supply Company in Kansas City, Missouri. Pepperdine would later found his namesake university in the hills of Malibu, California in 1937. Last, but not least, there is also the Morris family of Bass Pro Shops/Cabela’s fame from Springfield, Missouri, too – (something in that Ozark water…)

The Company estimates there are +37,000 auto parts locations in the U.S. The top-10 auto parts chains capture about 54% of these stores – up slightly from 48% back in 2012. AutoZone, O’Reilly and Advanced Auto dominate the industry with over 17,000 locations between them. The Company currently operates just over 6,000 stores in 48 states and Puerto Rico and 44 stores in Mexico. The Company opens between 175 and 185 new stores each year, most often in clusters, supported by a distribution center.

The U.S. auto parts industry is really two separate industries. The one we are most familiar with is do-it-yourself (DIY). The retail landscape has long been dotted by the ubiquitous stand-alone retail stores of the major public operators. For those living in small towns, one has surely been puzzled by the fact that three or four auto parts stores can survive, much less thrive in even the smallest of towns.

The other part of the industry is do-it-for-me (DIFM) – the most fragmented, and the larger driver of growth versus DIY. We are all too familiar with the situation where, when we take our car into the local auto repair shop for, say, a new set of tires, and the mechanic informs us that our brakes, shocks, etc. need to be replaced as well. That is when the differential elements of DIFM kick in. Every auto repair shop carries very little inventory on-site. Every repair shop, therefore, needs to call out to local auto parts companies, either public or private for the specific repair/maintenance needs for each car in each bay. Time is of the essence. Time is money. The parts manager must source parts as quickly as possible. Calls go out to the auto parts companies. Everything else being reasonably equal in quality and price, the auto parts company that can get parts to the repair shop the fastest gets the order. Fast, meaning no more than 30 minutes or so. Idle mechanics are a huge cost. Over time, these repair shop call lists are the bread and butter of the DIFM parts companies. Not only do you need to be on that call list, but if you perform well, you are then at or near the top of the ocean-front property call list. As such, DIFM customers can be a fountain of recurring revenues and profitability. They are for O’Reilly at least.

Amazon and Walmart are not significant competitors in the DIFM market. Their collective competition in the DIY is not a key factor either. Even the most die-hard DIYer need both local stores and informed advice – a key differentiation that both Walmart and Amazon struggle to match.

O’Reilly began its dual market strategy between DIY and DIFM back in 1978. Today, the split is about 60% DIY and 40% DIFM, with 6,027 stores in 48 states, 28 distribution centers, plus a small presence in Mexico (44 stores).

In order to thrive in the DIFM market – and O’Reilly is arguably the best public DIFM operator - an auto parts company must build and operate a capital-intensive, strategically dense distribution system of countless parts as close as possible to repair shops. O’Reilly operates a hub-and-spoke system, which includes 28 distribution centers, +275 “hub” stores, +90 “superhub” stores, and thousands of regular stores. The daily choreography between distribution centers, hub stores and smaller retail stores is as intense as one might assume. O’Reilly’s hub stores carry between 43,000 and 71,000 SKUs – smaller stores “just” 20,000 SKUs. Hub stores deliver parts to smaller stores multiple times every day and into the evening as well.

The DIY market is characterized by those with lower incomes with a single, even older model car. Such customers tend to attempt to maintain or fix simpler repairs on their own. DIY customers also tend to be more price sensitive than the time sensitive, demanding DIFM customers.

Many companies – too many, really – talk about “culture.” Rare is the company that can match O’Reilly’s culture. O’Reilly hires young. Dispenses significant responsibility at the store manager level. Promotes from within.

In July this year, the Company announced the near-term retirement of CEO Johnson, with his replacement of Beckham. In addition, Kirby moves to president. We expect these moves to be seamless.

The Company boasts that those employees with experience with at least one store EVP and three store SVP collectively amount to over 90 years. Those dozen-plus division VPs with industry experience collectively amount to over 300 years. This “family” culture has resulted in a very deep bench of multi-decade management ranks – yet was long planted by the O’Reilly family themselves. The Company’s culture-harvest has been bountiful.

O’Reilly also incentivizes management with cash bonuses not based on growth, but profitability – specifically return on invested capital. We hope management hears our loud applause.

O’Reilly’s dreams have manifested themselves into the reality of leading industry profitability – as well as leading profitability in all of retailing. The virtuous reinvestment of copious free cash flow back into the business at ever-expanding margins has enriched shareholders, all the while expanding the Companies size, scope and scale, furthering O’Reilly’s competitive advantages.

The Company’s consistently positive revenue growth over its dense network has resulted in consistent operating leverage. Since 2007, the Company’s operating margin has grown from 12% to 22%, its profit margin from 5% to 15% and its cash flow return on invested capital from 13% to 25%. In addition, the Company calculates its return on invested capital grew from around 11% in 2008 to 39% in 2019. During the pandemic, the Company thrived. Return on invested capital soared to 49%, 68% and 72%, in 2020, 2021, and 2022, respectively.

In the years ahead, we expect O’Reilly to continue to gain market share, grow its store count, comp sales at mid-single digits, and grow earnings at high single digits to low double digits. Growth by acquisition is quite limited these days. The Company’s earlier history was dominated by a number of expansive acquisitions building out a national footprint, including Hi/LO Automotive (1998), Mid-State (2001), Midwest Automotive Distributors, CSK Auto (2008), VIP Auto Parts (2012), Bond Auto Parts (2016), Bennett Auto Supply (2018) and Mexico-based Mayasa Auto Parts (2019).

O’Reilly’s nationwide footprint is still lacking a large presence in the Northeast, as well as the Atlantic coast. The Company noted that, as of late 2021, it typically operates a store in their network for every 56,000 people in the U.S. However, in the Northeast, it operates a single store for every 189,000 people. M&A opportunities may still exist to fill this gap. If not, organic growth to fill out this gap may take years to fill.

We applaud the Company’s long-held capital allocation discipline: reinvest into more ever profitable stores, pay zero cash dividends, and continue to hoover up the shares. We have long advocated for share buybacks to be executed at least at reasonable valuations, and with a fat bat when such pitches are fat themselves. Indeed, the Company has cut its share count in half just since 2013.

(Post-script: Some of the more aged investment team members at Wedgewood are selfproclaimed “gearheads.” Furthermore, we ardently proclaim the movie Smokey and the Bandit to be one of the best documentaries ever produced by Hollywood! We (ok, I) have watched the amazing O’Reilly growth story (AutoZone, too) unfold for too many years. We are delighted to finally be investors in O’Reilly.)

Merion Road Capital initiated positions in two new stocks this quarter, Summit Materials (SUM), and W.K. Kellogg (KLG). They briefly discussed each position in their latest letter.

During the quarter I established a new position in Summit Materials (“SUM”). SUM is a construction materials provider with about 40% of their revenue from aggregates and cement, 30% from ready-mix concrete, and the remaining from asphalt and paving. I have followed the aggregates and cement industry for many years and have always been attracted to it. What’s not to like given the lack of substitutes, limited competition due to permitting and transportation costs, and long-term demand growth. With the majority of product serving public construction needs, the industry should benefit from the recently passed infrastructure bills that have yet to truly hit the market.

In early September the company announced that they would acquire the U.S. operations of Cementos Argos, a Colombian cement company. The market did not like the transaction as SUM subsequently traded down over 20%. While this move was not entirely unwarranted, I thought it was excessive and used the sell-off to establish a position. To be fair, SUM paid up for the assets(10x EBITDA) and I wouldn’t be surprised if Argos had underinvested in them / they require additional capital. On the flip side, this acquisition will shift SUM’s business mix to the more stable and higher valued business lines of aggregates/cement. Furthermore, it increases the company’s exposure to growth states like Florida, the Carolina’s, and Georgia. Add in the potential of operational synergies and high-return capital investments, and this deal might not be so bad after all.

Since the quarter ended I have built a small- to mid-sized position in WK Kellogg (“KLG”). KLG is the North American business spun-out from the business formerly known as Kellogg. There is a ton of pessimism around this company. Two weeks before the spin the Wall Street Journal put out a scathing article on the cereal industry titled “It’s the Breakfast of Champions No More: Cereal Is in Long-Term Decline.” Unrelated, Ozempic and other GLP-1s have been a topic dejour and deemed to be a massive headwind to any unhealthy food product. Industry issues aside, KLG has recently performed worst amongst the big three (Post and General Mills being the other). In 2021 their production was stymied by a fire at their plant in Memphis and a strike by 1,400 people; production lagged and KLG generally lost share. Add in the fact that the spin accounted for only ~5% of the value of the parent company and it makes sense why most legacy shareholder receiving the stock would prefer to dump it into the market.

KLG owns highly recognizable and established brands like Frosted Flakes, Raisin Bran, Special K, Fruit Loops, and even Kashi for the health-conscious consumer. They have historically generated about $2.8bn in revenue but EBITDA margins were only in the mid- to high-single digits. Part of this can be explained by being a small part of a much larger company. Some brands were run separately from others, geographies were split, and the sales force was responsible for selling not just cereal but the whole arsenal of Kellogg product. By eliminating silos and having a dedicated sales force management hopes to drive margin improvement and regain lost share. More importantly, however, they plan to invest several hundred million into their outdated manufacturing facilities. Management is targeting a 5% margin improvement over the next couple years which would still leave them below Post, which operates in the 15%-20% range. If margins don’t move up much from here earnings are probably in the $0.75 range putting the stock at 13x. Assuming operating margins improve 3% off LTM figures (to account for any incremental depreciation expense) we would get to $1.50 in earnings or less than 7x. This all compares favorably to Post and General Mills multiples in the mid-teens. While there is a lot to dislike about KLG, the risk return seems attractive.

Upslope Capital initiated one new position during the third quarter — Ball Corp (BALL). Upslope is re-entering the beverage can manufacturer after selling in 2022 when they concluded they were too early. Is 2023 right on time?

Ball Corp (BALL) – ‘New’ Long

Ball is the leading global producer of beverage cans. Upslope was long Ball (briefly) in 2022 before I concluded it was too early. No doubt, the company is still facing challenges. Some are temporary and likely to reverse in the near-term (fully leveraged balance sheet, industry over-expansion, overly aggressive carbonated soft drink (CSD) pricing) or medium-term (Budweiser exposure). Others are highly uncertain (GLP-1 weight-loss drug impact) but are being priced with certainty, assuming no actions on the part of bevcan or CSD producers (e.g. Coke, Pepsi) to offset any still-hypothetical pain.

Importantly, Ball’s recent announcement that it is selling its Aerospace unit, which has no strategic relevance to the core bevcan business, for after-tax proceeds of ~30% of the company’s market cap, provides a hard catalyst for shares to stabilize in the year ahead. In addition to de-levering the balance sheet – more important than ever, given the rate environment – the divestiture provides Ball with significant firepower to resume buybacks. The transaction should close in 1H 2024 and seems well-aligned with a bottom or rebound across many of the issues Ball has faced of late.

Risks still remain – the issues noted above are all very real, but they are all well-known and mostly temporary, in my view. To be frank, we have already been whipsawed with the latest purchase, as I assumed the market would show more immediate appreciation for the divestiture. But the combination of: low valuation for an economically defensive business with troughing fundamentals and a significant cash windfall seems like an optimal setup for even moderately patient investors.

Until next time! - EP